While surfing through Instagram one evening, I stumbled upon an advert that seemed like a bizarre joke at first glance. The page specializes in selling second-hand items—mostly electronics, furniture, and clothes—but this particular post drew my attention instantly. It wasn’t just the item, but the image: a picture of a dilapidated shrine, featuring what seemed like weary-looking deities slumping in their wooden abode. Then, I read the caption:

“Complete Juju Shrine for Sale! Everything is intact. About 12 different gods, all working perfectly well. Price: N9.6 million Naira, slightly negotiable, with room for installmental payments. Location: IMODI-MOSAN, OGUN-STATE but can be waybilled via air or disappearance. Reason for sale: Owner relocating to Germany for greener pastures due to bad governance. A trial will convince you.”

I burst into an uncontrollable laugh! But after the initial amusement faded, I found myself staring blankly at the screen, the sarcasm hitting deeper than it should. A “fairly used shrine”? A “slightly negotiable price”? And yet, this was not just an isolated ad on social media but a disturbing metaphor for the commodification of religion, especially in Nigeria and Africa at large. Religion, which once stood for deep spirituality and communal sanctity, has evolved—or perhaps devolved—into something far more commercial.

The Evolution of Religious Commodification

As ridiculous as this advert seemed, it highlights a growing trend that many of us recognize but seldom address: the commercialization of faith and religious institutions. Across Africa, particularly Nigeria, religion has become big business. Gone are the days when religion solely provided spiritual guidance; today, it is an enterprise. Whether you belong to a mosque, church, or traditional shrine, the commodification is clear—prayers are for sale, miracles are monetized, and salvation is a lucrative market.

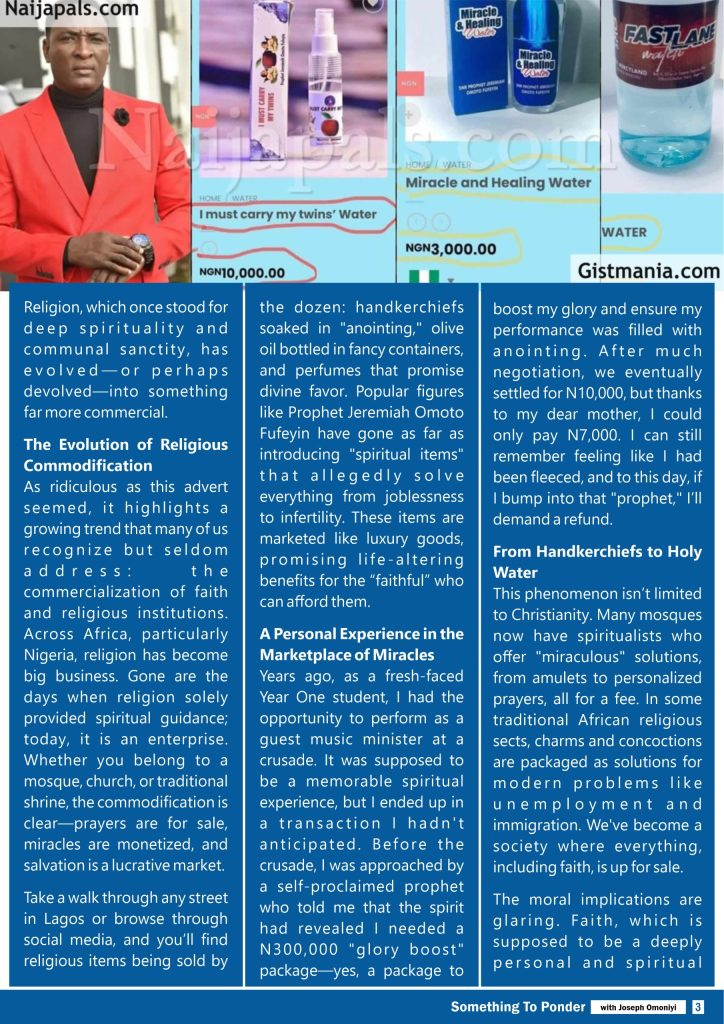

Take a walk through any street in Lagos or browse through social media, and you’ll find religious items being sold by the dozen: handkerchiefs soaked in “anointing,” olive oil bottled in fancy containers, and perfumes that promise divine favor. Popular figures like Prophet Jeremiah Omoto Fufeyin have gone as far as introducing “spiritual items” that allegedly solve everything from joblessness to infertility. These items are marketed like luxury goods, promising life-altering benefits for the “faithful” who can afford them.

A Personal Experience in the Marketplace of Miracles

Years ago, as a fresh-faced Year One student, I had the opportunity to perform as a guest music minister at a crusade. It was supposed to be a memorable spiritual experience, but I ended up in a transaction I hadn’t anticipated. Before the crusade, I was approached by a self-proclaimed prophet who told me that the spirit had revealed I needed a N300,000 “glory boost” package—yes, a package to boost my glory and ensure my performance was filled with anointing. After much negotiation, we eventually settled for N10,000, but thanks to my dear mother, I could only pay N7,000. I can still remember feeling like I had been fleeced, and to this day, if I bump into that “prophet,” I’ll demand a refund.

From Handkerchiefs to Holy Water

This phenomenon isn’t limited to Christianity. Many mosques now have spiritualists who offer “miraculous” solutions, from amulets to personalized prayers, all for a fee. In some traditional African religious sects, charms and concoctions are packaged as solutions for modern problems like unemployment and immigration. We’ve become a society where everything, including faith, is up for sale.

The moral implications are glaring. Faith, which is supposed to be a deeply personal and spiritual experience, is now subjected to the same market dynamics as consumer goods. Worshippers are treated as customers, and pastors, imams, and priests have become businessmen. The line between devotion and exploitation is increasingly blurred.

The Economy of Faith

In a country where poverty levels are staggering, the booming economy of religion is both fascinating and troubling. Nigeria’s religious industry is worth billions. Churches, mosques, and even traditional worship centers rake in considerable sums through offerings, tithes, and “special” donations. You see, faith-based enterprises now employ the same strategies as multinationals—emphasizing brand loyalty, market expansion, and aggressive advertising. The faithful, often desperate for miracles in a country where governance has failed them, willingly part with their hard-earned money, hoping for divine intervention in their lives.

Some may argue that it’s not the sale of these items that’s inherently wrong but the way religion has become a marketplace of false promises. After all, how many of these “miracle products” actually work? And if they don’t, why are they still flying off the shelves? Perhaps it’s the same psychology that drives people to play the lottery—hope is a powerful motivator.

The Future of the Faith Market

As we march further into this religious commercial age, what can we expect? The answer is simple: more of the same, and likely worse. With the advent of technology, religious commodification has found fertile ground on social media. Pastors now have YouTube channels, and prophets advertise their products on Instagram. Soon, we may even have religious apps where you can subscribe for a weekly miracle or request an on-demand prayer service.

This rise of religion as a transactional enterprise makes one wonder: how much longer before the gods themselves get tired of being “fairly used”?

Rhetorics to Ponder

- When did faith become a product you can price-tag?

- What happens to the spirituality of a religion when it is commodified?

- Can we still trust the motives of religious institutions when their primary goal seems to be profit?

Don’t miss: Is Dangote Selling Fuel or Vodka?

While I laughed hard at the advert for the “second-hand” shrine, it gave me pause. How many of us have bought into commodified faith? At the end of the day, we’re left asking: In a world where everything has a price, is there any room left for true devotion?

.